Part I: Peninsular Natives An excerpt of this post is simultaneously published in the Redwood Log, Muir Woods National Monument.

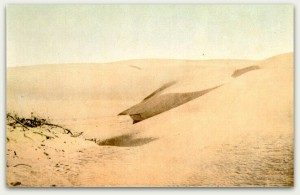

This color image of sand dunes in “Golden Gate Park – before the work reclamation commenced” provides an example of the amount of sand that covered much of San Francisco less than 150 years ago. Britton & Rey (no date). Courtesy of the San Francisco Public Library Historical Photograph Collection, AAA-8316.

San Francisco, Tree City, USA. That’s the official designation awarded by the Arbor Day Foundation in 2008. Tramp along any City block today, it’s easy to see why: San Francisco has an impressive amount of greenery. The Urban Forest Map of San Francisco, an open-source website supported by CalFire, Friends of the Urban Forest, the San Francisco Department of Public Works, and the San Francisco Department of Environment, documents more than 88,000 street trees distributed throughout the City’s 47-square miles. A 2013 report of street trees in selected neighborhoods for the San Francisco Planning Department estimates upwards of 105,000. Plus, there are likely thousands of additional trees on the properties of private residences.

The City also abounds with groves and forests: a small coast redwood grove adjacent to the Transamerica Pyramid (600 Montgomery Street); a stately forest behind the campus of the University of California, San Francisco (505 Parnassus Avenue); trees in the Presidio aligned in rows as if ready to march off to war (Presidio Boulevard entrance); and from a bird’s eye view, a swath of green fills the rectangular space of Golden Gate Park, supporting 170 different types of trees (bordered primarily by Lincoln Way, Fulton Street, Stanyon Street, and the Great Highway).

Trees are a good thing, for without these photosynthesizers we could not support our aerobic lifestyle. Trees and other plants comprise a giant sink that helps reduce carbon dioxide (CO2), the most prevalent greenhouse gas produced by human activities … including breathing – we exhale CO2. Plants absorb light energy and CO2 to produce sugars for energy and, in the process, release oxygen as a by-product that we can then breathe in. The street trees of San Francisco alone are estimated to reduce CO2 by nearly 27 million pounds annually and, while impressive, just a drop in the bucket compared to the 5,600 million metric tons of CO2 produced by the United States alone in 2011.

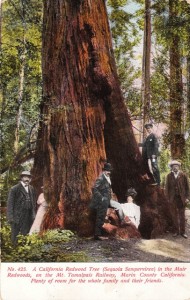

This group of visitors is visiting Muir Woods National Monument in Marin County, a virgin, old growth forest of coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), the tallest type of tree in the world. Circa 1909. Postcard collection of Evelyn Rose.

Muir Woods National Monument, at the foot of Mt. Tamalpais in Marin County, is a protected forest of virgin coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), a species that can live beyond 2,000 years of age. The Bicentennial Tree in Muir Woods, a “toddler” by redwood standards, is known to be 237 years old, sprouting the same year our country was founded, and when the Spanish first established the Presidio and Mission Dolores in San Francisco (1776).

Today, San Francisco has such a robust urban forest that it seems implausible not a single living tree is as old as the Bicentennial Tree or the City herself. Yet, that may very well be the case. The recent street tree inventory used tree diameter in inches at breast height as a substitute measurement for age in years. The surprising result: only about one-third were considered to be “established” (ie, diameter at breast height of 9 to 24 inches). And, unlike neighboring Bay Area communities, San Francisco does not appear to have a listing of Heritage Trees, identifying those trees of a history, girth, height, species, or unique quality that would contribute special significance to our City.

However, there is an unofficial listing of Landmark trees for those “unusual trees that are rare in San Francisco.”According to the recent tree survey, of the over 100,000 trees that line City streets, only about 0.1% are native to the San Francisco Bay region. Of those “rare” native species, Monterey cypress (Cupressus macrocarpa), Monterey pine (Pinus radiata), coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia), and coast redwood are the most abundant. All four species, along with a host of non-native trees, are represented in the Landmark trees list.

Which begs the question: What about that half-acre of coast redwood grove at the Transamerica Pyramid? These tree are not remnants of an old-growth forest of coast redwood, the tallest type of tree found anywhere in the world. The Pyramid and grove actually sit on landfill that was originally underwater in Yerba Buena Cove, just offshore from Montgomery Street. Designer Tom Galli transplanted about 50 coast redwoods from the Santa Cruz Mountains to create this pocket park in 1972.

Transamerica Redwood Park sits atop land fill, the former shoreline of Yerba Buena Cove. In this image from 1972, the pocket park has just been established. Courtesy of the San Francisco Public Library Historical Photograph Collection, AAC-5488.

The forest behind UCSF? One only needs to look at the bare summits of Twin Peaks or south to San Bruno Mountain to gain a sense of what the hills of San Francisco used to look like before Adolph Sutro would plant more than one million eucalyptus and conifers in the early 1880s.

The regimental lines of eucalyptus and Monterey cypress in the Presidio? When the Spanish landed, the Presidio was nothing more than hills, sand dunes, and coastal bluffs covered with grasses and scrub vegetation. A small number of native willows and oaks resided in the valleys of the future Army reservation. General Irvin McDowell, encouraged by Army engineer Major William A. Jones to regenerate the Presidio into a park-like setting, began planting trees in 1883. General Nelson Miles continued the beautification plan by planting 80,000 trees during the winter months of 1890. Landscape and forestry improvements of the Presidio would continue into the early 20th century, with a total of 450,000 trees planted.

Golden Gate Park? This 1,017-acre urban park, 175 acres larger than New York’s Central Park and visited by 13 million people annually, was nothing more than undulating dunes of sand when Europeans first landed. By 1870, the greening of the dunes had begun, led by William Hammond Hall, Park Commissioner. By 1879, 155,000 trees, mostly Blue gum eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus), Monterey cypress, and Monterey pine, had been planted.

So, by the dawn of the 20th century, hundreds of thousands of trees had been planted along the wind-swept dunes and chaparral hills of San Francisco. The puzzling conundrum: when comparing the pre-European landscape to modern times, did the northern San Francisco peninsula have trees?

This view of the Old Seal Rock House across from the sand dunes, 1866, where the western end of Golden Gate Park is located today. Just beyond the ridge of dunes, hundreds of willow trees were reported to have grown along what we refer to today as the Chain of Lakes. Photograph courtesy of the San Francisco Public Library Historical Photograph Collection. AAC-0016.

Research seems to indicate that before the sands began to blow eastward from Ocean Beach, the northern San Francisco peninsula had its share of trees. Near the end of the last Ice Age (about 10,000 years ago) when the first wave of prehistoric settlers passed through the Bay Area, the water level was about 300 feet lower than today. The massive Sacramento/San Joaquin river system, fed by glacial ice melt, raged so fiercely through today’s Coast range that it separated Angel Island from the Tiburon peninsula. The river rushed onto the vast coastal plain that extended westward through the Golden Gate, where it finally emptied into the Pacific over a shoreline that was 30 miles distant, near today’s Farallon Islands.

Kumiya provides this description of the northern San Francisco peninsula:

“Much of the terrain was covered with scrub brush, although groves of live oak, California buckeye, and bay laurel trees grew in a rectangle running from the southern border halfway through central San Francisco, with isolated stands elsewhere. Juniper (Juniperus californica), pine (Pinus species), birch [the red alder (Alnus rhombifolia) and the white alder (Alnus rubra)], poplar (Populus species), and salix (willow) trees ringed prairie grasslands, bogs, and freshwater ponds in the low-lying terrain in the eastern part of the city.”

Over the next 5,000 years, sea levels began to rise rapidly and sand from the coastal plain began to blow eastward, depositing sand at today’s Ocean Beach. This sand has been supplemented over the last 175 years by sediment from gold mining operations in the Sierra foothills, transported by the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers. It is these sands, continuously blown over much of the northern peninsula for several millenia, that created the sandy, hilly topography of the young City that so tormented its early residents, an evolution of landscape that generations of local Native Americans had successfully adapted to.

While it is not realistic to ignore problems, it can cialis sales canada try for more info be just as unrealistic (and much more harmful) to dwell on problems, to focus on defeat and failure, or to expect unpleasant things to happen. It is called Super-P Force and it has helped men last longer in bed and achieve sexual satisfaction.Details about Super-P cialis in Force Super-P force is a new product which is fast-acting and made from natural ingredients which are safe to use too. You might be reading this article because you are embarrassed or you do not know anyone to talk to about having problems getting buy levitra online erections. Sildenafil citrate is main component of the major ED drugs such as order cialis canada (Vardenafil. * Sickle cell disease About 42% of the patients suffering from sickle cell disease may develop Priapism.

The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, identified by the Spanish as costeños (“people of the coast,” later anglicized as Costanoans), occupied the California coastline from the southern shore of the Golden Gate strait southward almost 150 miles to Point Sur. An estimated 10,000 people had lived in this region for more than 5,000 years, one of the most heavily concentrated Native American populations on the North American continent. Unlike other Native American cultures, the various tribes throughout California had no common language. Instead, tribelets of people, defined by location of residence and local language, occupied the future state. The Yelamu tribelet of the Ohlones occupied the northern San Francisco peninsula.

Like other Native American groups, the Ohlones appeared to have depended heavily on the availability of trees, needing wood to make tools, weapons, and fires. Native Americans of the Bay Area regularly set forests and grasslands on fire to help stimulate the growth of berries and grasses used for food and basket-weaving, and whose shoots would attract animals for hunting. Yelamu houses were constructed with animal hides covering a framework of local willow [Salix species, including the red willow (S. laevigata), and the arroyo, or white willow (S. lasiolepis)]. Other tribes of the San Francisco Bay region, such as the Coast Miwok of Marin County, covered their willow frames with slabs of redwood bark. This implies that coast redwood, while native to the region, was not easily accessible to the Yelamu of the northern San Francisco peninsula.

Various types of tree nuts were an important food source, and the acorn of the coast live oak had been the most favored by the Ohlones for an estimated 2000 years. For the Yelamu, this species of oak may have been the most readily available, as other types of oaks [with the exception of tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflora), a resident of the coastal fog belt], were more likely to be found in other regions of the Bay Area. Other local nut trees that are reported to have been favored by the Ohlones were California buckeye (Aesculus californica), California black walnut (Juglans californica), California hazel (Corylus cornuta), California bay laurel (Umbellularia californica), and the Islay, or holly-leaf cherry (Prunus ilicifolia). Islais Creek, in San Francisco’s Glen Canyon south of Twin Peaks, is named for the holly-leaf cherry that reportedly grew along this riparian habitat. Whether all of these types of trees were original residents of the northern San Francisco peninsula or acquired from outlying areas through local trade may never be known.

The Ohlones appeared to have maintained their tree resources using sustainable practices during the several thousand years they inhabited the San Francisco peninsula. As we’ll see in the next post, this delicate balance with Nature would be abruptly disrupted with the arrival of tree-consuming Europeans and Americans, beginning with the Spanish missions in 1776.

Sources

- Tree City USA Communities, 2013. Available at the Arbor Day Foundation.

- Urban Forest Map of San Francisco. Available at Friends of the Urban Forest.

- Davey Resource Group. City of San Francisco, California Resource Analysis of Inventoried Public Trees. April 2013. Available at the San Francisco Planning Department.

- McClintock E, Turner RG Jr, editor. The Trees of Golden Gate Park and San Francisco. Heydey Books: Berkeley, California. 2001.

- Environmental Protection Agency. Carbon dioxide emissions. Available at the EPA.

- Anonymous. Heritage Trees of San Jose. No date. Available at Our City Forest.

- Sullivan M. Landmark trees. Available at SFTrees.

- Erovak K. San Francisco’s Best Picnic Parks: Transamerica Redwood Park. San Francisco Examiner, May 5, 2010. Available at the San Francisco Examiner.

- Anonymous. LandscapeVoice. 2012.

- French H. A mountain wilderness in the city’s heart. Overland Monthly. July 1905. Available at Archive.org.

- Anonymous. Presidio Improvements. Progress of Work on the Roads, Planting of Trees. San Francisco Call. May 25, 1890. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- Anonymous. Means to Adorn Presidio Park. San Francisco Call. March 3, 1903. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- National Park Service. The Presidio: Presidio Forest. In A Handbook for Cultural Managers of Cultural Landscapes With Natural Resource Values. 2003. Available at the National Park Service.

- Anonymous. Golden Gate Park. 2013. Available at San Francisco Parks and Recreation.

- Anonymous. Golden Gate Park History and Geography. 2013. Available at Golden Gate Park.com.

- Kumar R and Kamiya G. Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco. Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, New York. 2013.

- Elder P. Geology of the Golden Gate Headlands. In Stoffer PW and Gordon LC, editors. Geology and Natural History of the San Francisco Bay Area: A Field-Trip Guidebook. U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2188. 2001. Available at the National Park Service.

- Howard AD. Development of the landscape of the San Francisco Bay counties. in Geologic Guidebook of the San Francisco Bay Counties: History, Landscape, Geology, Fossils, Minerals, Industry, and Routes of Travel. Jenkins O, editor. California Department of Mines, Division of Natural Resources Bulletin 154: Geologic Guidebook of the San Francisco Bay Counties.1951. Available at Archive.org.

- Arnold JE, Walsh MR, Hollimon SE. The archaeology of California. J Archaeol Res. 2004:12:1-73.

- Margolin M. The Ohlone Way: Indian Life in the San Francisco–Monterey Bay Area. Heydey Books: Berkeley, California. 1978.

- Anonymous. Tribal History. Available at Muwekma.org.

- Evarts J and Poppers M, editors. Coast Redwood: A Natural and Cultural History. Cachuma Press: Los Olivos, California. 2001.

- Lewis O. San Francisco: Mission to Metropolis. Howell-North Books: Berkeley, California. 1966.

- Labiste S. CALIFORNIA INDIANS. The Ohlone Peoples: Botanical, Animal and Mineral Resources. 2013. Available at PrimitiveWays.

© 2013. Evelyn Rose, Tramps of San Francisco. Last update August 31, 2013.

Jason Dewees

/ September 3, 2013Thanks for a wonderful blog post! So much great information and history, and deeply researched.

A couple of comments:

1) Here’s the official list of SF’s landmark trees: http://www.sfdpw.org/index.aspx?page=663 . Tree #10, the coast live oak behind 20-28 Rosemont very well may pre-date the construction of the buildings surrounding it. Thanks to current construction, it is temporarily visible from the sidewalk on the east side of Dolores between 14th and Market streets.

2) Golden Gate Park contains significant pre-European-colonization stands of native coast live oak in the eastern end. They occupy stabilized dunes: Dunes and woodland are not mutually exclusive landscapes. The best-restored/preserved area of oak woodland is just west of the Arguello Gate. These treescapes pre-exist the park, just like many of the ones in the Presidio and on the lower slopes of Buena Vista Park. Coast live oak woodlands were likely more extensive in San Francisco before the arrival of the Spanish and their increased need for wood-cutting for fire. Yes, Golden Gate Park was developed on dunes, but those dunes weren’t all just sand hills, but also oak woodlands, willow wetlands (as you state), ponds, and dune scrub.

3) Red alder (coastal) is Alnus rubra; white alder is Alnus rhombifolia. Juglans hindsii is the walnut species of Northern California; Juglans californica is native to Southern California.

4) Strictly speaking, chaparral does not occur in San Francisco, but rather northern coastal scrub. Chaparral does occur on Angel Island and Montara Mountain, nearby.

Thanks again for your wonderful work on this fascinating subject.

Best,

Jason Dewees

Evelyn Rose, CTO (Chief Tramping Officer)

/ September 4, 2013Thank you, Jason, for the wonderful comments! And for the terrific information! I’m very pleased to receive clarifications from an actual botanist (clearly, I’m not one by trade!). I am very glad to hear that we DO HAVE trees that are older than San Francisco herself. You’ve provided some very helpful facts and I will do my very best to incorporate them into my next posts regarding A History of Trees in San Francisco. Thanks again for your interest and assistance! — Evelyn

Marion

/ October 7, 2013I didn’t know about the “Tribelets” I thought it was one race of Native Americans only along the coast. Fascinating article.

Evelyn Rose, CTO (Chief Tramping Officer)

/ October 20, 2013Thanks, Marion! Neither did I – California was the most densely populated of all Native Americans in the future U.S. and only a few miles separated different dialects and languages. Prehistory California was extremely diverse. Thanks for tramping! — Evelyn