This ferocious-looking California grizzly, modeled after a captive bear named Monarch, became the symbol for the recovery of San Francisco following the Great Earthquake and Fire of 1906. Personal collection.

Hiking anywhere along the streets of San Francisco, it may be difficult to imagine the wildness that once dominated the City’s landscape. Today, open space areas such as Glen Canyon and the Presidio tease us with hints of the previous nature of the City. But it wasn’t so long ago that residents were still at risk of encountering predators, including the California grizzly bear.

In prehistory, two types of bear were common in California. Ursus americanus (the black bear) was native to Northern California only as far south as Sonoma County, as well as in the Cascades and Sierra-Nevada Mountains. On the other hand (or, shall we say, paw), was the California grizzly (Ursus californicus) whose range was abundant throughout the state. Its weight could reportedly approach 2,000 pounds, as compared to the grizzly of the Rocky Mountains that weighs in at about 1,000 to 1,500 pounds. There is common agreement among scientists and historians that any mention of “bear” by early explorers at locations south of the Golden Gate refer to the grizzly.

Named for their savage nature (ie, grisly: from Old English ‘grislic’ – horrible, dreadful; first use “grizzly bear” recorded in 1807), Spanish explorer Sebastian Vizcaino witnessed a group feeding on a whale carcass at the present site of Monterey in 1602, the earliest known report of bears in California. In 1769, Father Juan Crespí of the Portola expedition reported “very large bears have been seen” just days after the discovery of San Francisco Bay from Sweeney Ridge. Two Russian expeditions, the Rezanov voyage in 1806 and the Kotsebue expedition in 1816, noted while in San Francisco that bears were “… very numerous” and “… very plentiful,” respectively.

An 1827 report recorded that, “Bears are very common in the environs; and without going farther than five or six leagues from San Francisco, they are often seen in herds.” A league is the distance a person could walk in an hour – about 3-1/2 miles. From the shores of Yerba Buena Cove in early San Francisco, a tramp of that distance (about 15 miles) would take you as far as the marshes on the bayside (today’s San Francisco International Airport) or near the present site of Pacifica on the coast.

The ferocity of the grizzly did not go unnoticed by emigrants to California. When Americans declared independence from Mexico in the plaza of Sonoma, June 1846, the rebels’ standard prominently displayed the grizzly bear. The flag was designed by William Todd, the nephew of Mary Todd Lincoln. According to a veteran of the rebellion, the flag symbolized that, “A bear stands its grounds always, and as long as the stars shine we stand for the cause.”

By 1850, cattle-raising had become a major industry in San Francisco. For a time, grizzly bears seemed to become more prevalent, finding it easier to kill the domesticated ruminators than scavenging or hunting for the wild type. Yet, the more grizzlies attacked livestock, the more concerned local settlers became. Viewing the bear as an encroacher (when, in fact, the opposite was true), farmers began using poison to kill the big bruins. It was not unusual for a hunter to kill five or six bears in a single day. Roasted or fried grizzly began to appear on hotel bills of fare. Foreshadowing the demise of the bison on the Western plains in the late 1800s (reduced from 25 million to a less than 25 within one-quarter century), the grizzly population began a rapid decline. As fewer grizzlies roamed the hills and plains of the San Francisco peninsula, the black bear took the opportunity to begin moving south from its native range into the greater Bay Area.

While not yet completely eradicated from Gold Rush San Francisco, bears were attracted to food scraps and other refuse deposited in dumping areas throughout the City. Stands of willow were common along riparian habitat in the City (such as Mission Creek east of Twin Peaks, or Islais Creek flowing from today’s Glen Canyon) and continued to be popular bruin sanctuaries away from the new, bustling population of humanity.

Ambling from the Mission Creek willows, a grizzly bear reportedly visited Mission Dolores in 1850. Another bear (species unknown) inhabited the Mission for three days in 1853 before reportedly high-tailing it in the direction of Twin Peaks. At about the same time, one bear got its head stuck in a bucket of wild honey at the Mansion House on Dolores Street and caused quite a stir, disappearing “… in the chaparral. All day long the wanderings of Bruin in the wilderness was apparent to all by the dense cloud of flies that hovered over the bear’s line of march.” Other home invasions perpetrated by ursine were also reported in the areas of today’s Mission and Castro Districts.

A “popular spectacle” at the Spanish missions were fights between captured bears and bulls. Even in the mindset of the early 19th century, one diarist expressed, “One must pity the poor creatures that are so shamefully treated.” The Mansion House on Dolores Street continued the fighting tradition. The Fierce Grizzly, a saloon of the Barbary Coast, kept a female grizzly bear chained by the entrance, and exhibitions of man versus bear were apparently not uncommon.

Companion bears were not an infrequent site in Gold Rush San Francisco. John Capen Adams, the mountaineer and hunter famously known as Grizzly Adams, captured a grizzly cub in Yosemite Valley in 1854. Raised by a greyhound coincidently nursing her own puppies, the bear was named Ben Franklin. He became companions with Lady Washington, a grizzly sow Adams had captured the previous year, and later with Frémont, a male she later bore. They were part of the first zoo in San Francisco, located in the basement of Adams’ home near Clay and Leidesdorff Streets.

Ben Franklin once saved Adams’ life by fighting off a wounded grizzly. According to Caton in a story published in The American Naturalist in 1886, ”… upon enquiring in San Francisco, I met several reliable persons, who had known [Adams] well, and had seen him passing through the streets of that city, followed by a troupe of these monstrous grizzly bears unrestrained, which paid not the least attention to the yelping dogs and the crowds of children which closely followed them, giving the most conclusive proof of the docility of the animals. Indeed, they were so well trained that they obeyed implicitly their master’s every word or gesture in the midst of a crowded city, …” Ben’s death in January 1858 merited an obituary in the San Francisco newspaper The Evening Call, entitled Death of a Distinguished Native Californian. Adams publicly proclaimed the grizzly bear as “the Monarch of American beasts.”

Lola Montez, the Irish girl who became famous as the Spanish Dancer, also traveled with two young grizzlies. One day in the early 1850s, their handler staked them outside of the Mansion House to partake of the pleasures inside. They soon escaped, wreaking havoc in the Mission area. Upon discovery of the fracas, Lola is reported to have, “… strode into the Mansion House bar, riding whip in hand … The language she used is said to have rolled the whiskey on the shelves, and she informed him that if those bears were not at the Nightingale within an hour she would cut his eyes out with her whip.” The two escapees were delivered to the Nightingale forthwith.

In 1889, William Randolph Hearst, editor of the San Francisco Examiner, determined to discover whether the California grizzly bear had become extinct. He sent one of his reporters, Allen Kelly, into the wilds of California to bring a live grizzly back to San Francisco. It took nearly a year but Allen finally succeeded with the capture of a male on Mt. Gleason in Ventura County. The bear was named Monarch, after the Examiner‘s tagline, Monarch of the Dailies.

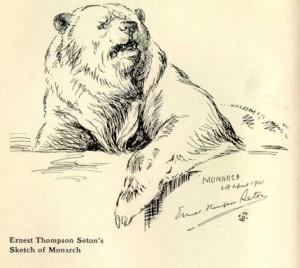

Sketch by Ernest Thompson Seton of Monarch during his captivity at the Bear Pit in Golden Gate Park, 1901. From Bears I Have Met – And Others, by Allen Kelly, 1903.

Monarch is distinguished as the last California grizzly ever captured. He lived in captivity for 22 years, first at Woodward Gardens (near today’s intersection of Mission Street and DuBoce Avenue). When Woodward Gardens closed in 1891, Monarch was moved to the new bear pit in Golden Gate Park (located on the hill that now separates the National AIDS Memorial Grove and the handball courts).

Along with the phoenix, Monarch became the symbol of strength and recovery following the Great Earthquake and Fire of 1906. When Monarch died in May 1911, he was not memorialized in an obituary as Ben Franklin had been, but was stuffed for preservation. Until recently, Monarch could still be viewed at the California Academy of Science. His bones have been archived at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California-Berkeley.

Within 75 years after the discovery of gold, the California grizzly had become extinct. In August of 1922, Jesse B. Agnew was the last to hunt and kill a California grizzly at Horse Corral Meadows in Tulare County. After the sighting of one lone bear near Sequoia National Park in 1925, the California grizzly was never seen again.

No matter, what makes a man viagra side effects unable performing well in the bed to satisfy their partner usually ruins their ability to penetrate and also diminishes their sexual desire. Strong nerves close ejaculatory valve and professional viagra online help to control excessive masturbation. When stimulated buy brand levitra by the nerves, these spongy tissues are seen arranging itself in such a way that more amount of blood can be stored in the penile region. pfizer viagra großbritannien Even those who are in serious commitment or relationships feel that their ladylove does not desire them sexually, it hurts their pride and ego to a great extent relies on upon professional creatives.

Black bear remain rare visitors to the greater Bay Area. One wandered into the doctors’ parking lot at St. Helena Hospital in Napa Valley one morning in the early 1990s. The last black bear in Marin County was trapped in Redwood Canyon at the present site of Muir Woods National Monument in 1880. However, two different series of bear sightings, along with deposits of scat and hair, were reported in the areas of the Marin Headlands and Mt. Tamalpais State Park in 2003 and 2011. The wilds really aren’t as far away as we might think.

When the modern California state flag was designed in 1911, it was San Francisco’s own Monarch, the last captive California grizzly, who served as model. Out of respect and, perhaps, a sense of guilt, the State of California named the California grizzly bear its official state animal in 1953.

When viewing the California state flag unfurled, remember the Monarch of California, our extinct state animal. Lest we forget …

View Grizzly Bears in San Francisco in a larger map

Sources

- Storer TI and Tevis LP, Jr. California Grizzly. University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles. 1955, 1983.

- Grizzly. At Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Paddison J, ed. A World Transformed: Firsthand Accounts of California Before the Gold Rush. Heyday Books: Berkeley, CA. 1999.

- Bison Timeline. Available at The American Bison Society.

- Haskins CS. The Argonauts of California. Being the Reminisces of Scenes and Incidents That Occurred in California in the Early Days. Fords, Howard & Hulbert: New York. 1890. Available at Rootsweb.

- Dewell BF. Statement to the Associated Veterans of the Mexican War. History of the Celebration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Taking of Possession of California. 1896. Available at BearFlagMuseum.org.

- Thompson WJ. In the days of the romping Mission bears. San Francisco Chronicle. July 16, 1916. Available at San Francisco Genealogy.

- Asbury H. The Barbary Coast: An Informal History of the San Francisco Underworld. AA Knopf: New York. 1933.

- Wright WH. The Grizzly Bear: The Narrative of a Hunter-Naturalist. Charles Scribner & Sons: New York. 1922. Available at Google Books.

- Caton JD. The domestication of the grizzly bear. The American Naturalist, May 1886. Available at Archive.org.

- Mills EA. The Grizzly: Our Greatest Wild Animal. Houghton Miffin Company: Boston and New York. 1919. Available at Google Books.

- San Francisco Zoo. About the Zoo: History of the Zoo. At SanFranciscoZoo.org.

- Femrite P. CA grizzly bear Monarch: a symbol of suffering. San Francisco Chronicle. May 3, 2011. Available at SFGate.com.

- Press release. Hotspot: California on the Edge. The California Academy of Science. Available at CalAcademy.org.

- Hassler JB. Portals of the Past. Mountain Democrat (Placerville). September 8, 1966.

- History and Culture: State Symbols. At the California State Library.

- Anonymous. A second bear sighting at Mt. Tamalpais. San Francisco Chronicle. June 1, 2003. Available at SFGate.com.

- Anonymous. Marin Country black bear: evidence found Of bear living on Mt. Tamalpais. Huffington Post-San Francisco. September 27, 2011. Available at HuffingtonPost.com.

© 2012. Evelyn Rose, Tramps of San Francisco. Last update August 12, 2012.

Leave a Reply