Part II: Dame Nature Has Done Her Part

“Next to the Klondike excitement, the subject which is creating the greatest local interest is that of a Mission Park.”

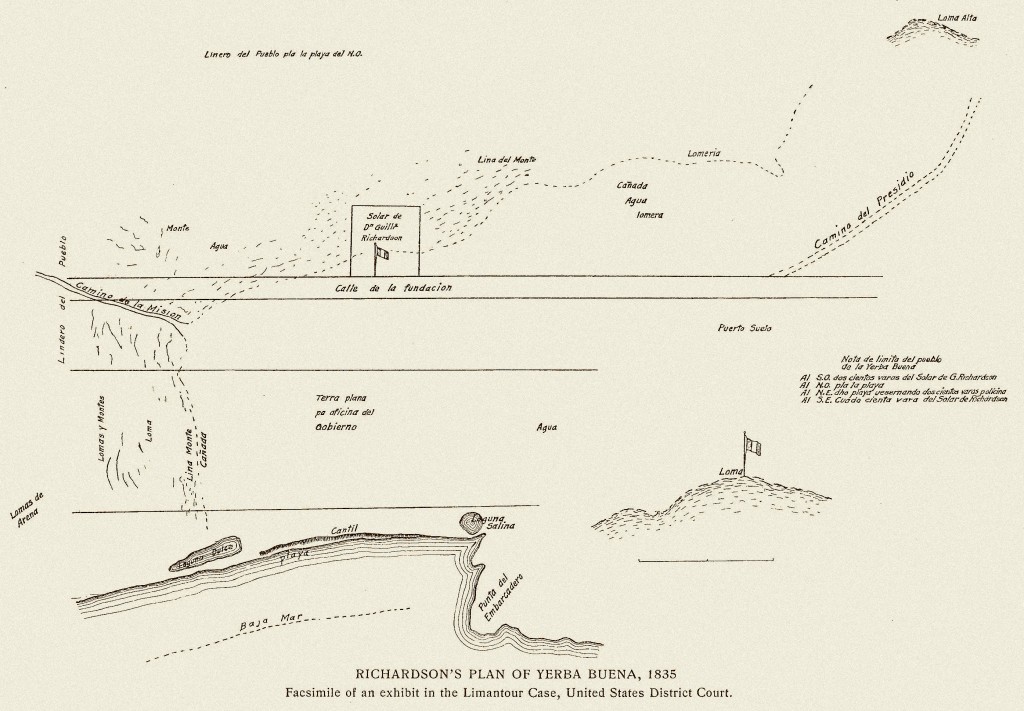

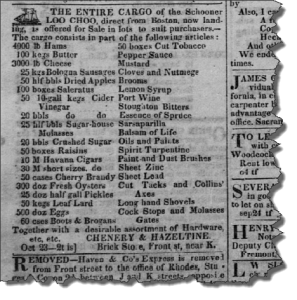

Design for the new Mission Park Zoo in Glen Park’s Gum Tree Tract by prominent San Francisco architect Frank S. Van Trees in 1897. In the “Italian renaissance” style, the zoo would have 38 cages of various sizes for the proposed menagerie. In the San Francisco Daily Report, August 7, 1897. California General Subject Collection. Courtesy of the Alice Phelan Sullivan Library, Society of California Pioneers. (Click image to enlarge)

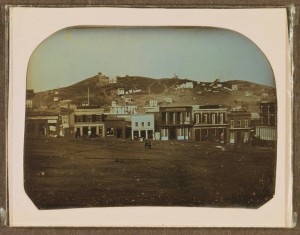

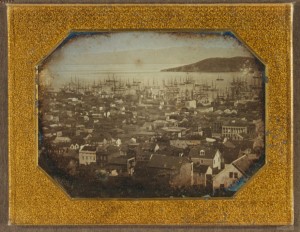

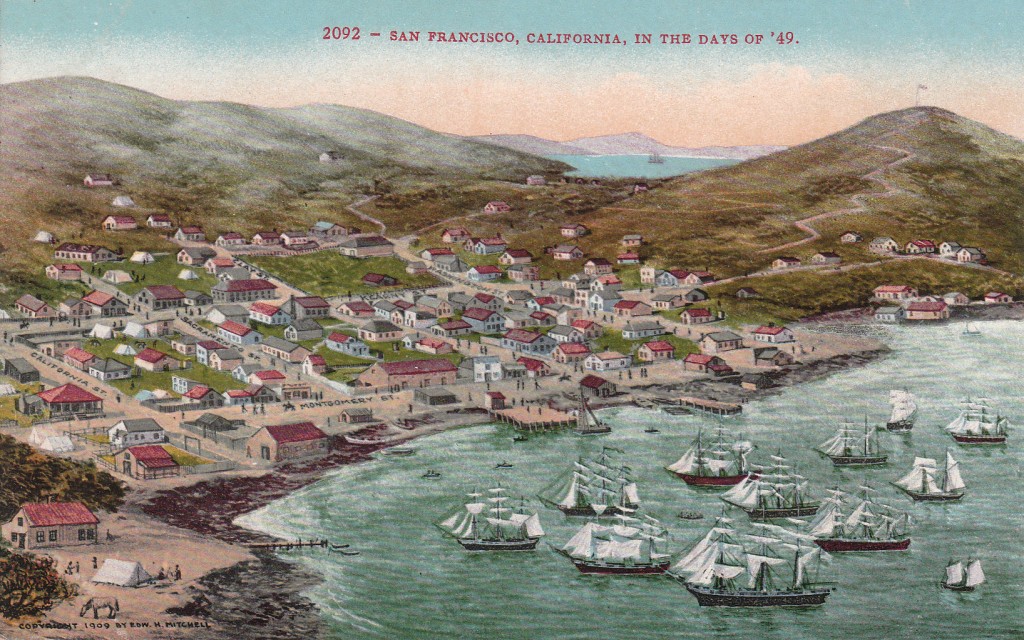

Those who knew and loved the Gum Tree Grove in the area of today’s Glen Canyon claimed, “Dame Nature Has Done Her Part.” The tract was treasured for “… its fine climate, its diversified topography and its accessibility to all parts of the City.”While the Supervisors ultimately rejected the land purchase and chose instead to use appropriations for the improvement of roads, schools, and utilities, the fondness with which supporters spoke of the Gum Tree Tract provides us with deeper insight as to what the neighborhood of Glen Park used to be like. Concurrently, a grand design for the new zoo by a leading San Francisco architect portrayed what supporters back in the day wished the future for Glen Park would hold.

Members of the Fairmount Improvement Club, adjacent to the proposed grounds, agreed that,

“The gum-tree tract is the place. We want crowds to visit the Mission. A zoo there will bring the people here. Many live near the grove, and can walk there. The streetcars pass it. Those who want to drive there can do so, and after passing through can drive on to the Golden Gate Park and to the Balboa road without having to go three miles out of their way. It is the natural outlet and driveway from the Mission to Golden Gate Park.”

It was also noted that there were,

“… about 100,000 trees of various kinds on the grounds … the entire land is filled with natural springs and running water. This item alone would save the City at least $6000 per annum.”

In their opposition to the suggestion by oppositional Mission residents that the more suitable location was “… in the vicinity of the Jewish Cemetery property, which consists of two blocks of land between Eighteenth and Twentieth, Church and Dolores streets” (today’s Dolores Park), the Fairmount Improvement Club resolved that,

“… a large park and a zoo will bring more people to the Mission and afford more enjoyment to a larger number than a mere square; … the ‘Gum-tree Tract’ is well adapted for the purpose of a park and a zoological garden …”

The Fairmount Improvement Club, among others, also opposed the price of the Jewish Cemetery property, an enormous $300,000 for just 14 acres in 1897, compared to Baldwin and Howell’s 145-acre Gum Tree Tract, offering 131 additional acres for only $87,500 more.

Other residents, such as druggist John H. Dawson (whose business was located at Twenty-second and Valencia and who had been a Mission resident for 20 years) noted that the Mission Park would, “… insure to the City a magnificent zoological collection and be a boon to and a source of pride to the whole City …” and “… would form an attraction that would be reckoned among the resources of the coast.” Patrick Wall, a Mission resident and large land owner “since the early days” pointed out that,

“The northern part of San Francisco is well supplied with parks. Not only is Golden Gate Park available, but the Presidio and Black Point reservations and Sutro Heights answer the same purpose. No part of the Western Addition is at an inconvenient distance from some agreeable breathing place. But further south, where the need is greater, there are no such opportunities. There are bare, open spaces as yet, but even these will disappear in time if we do not save some of them from the advance of the builders.”

J. Murray, a merchant in the Mission district, responded to the claim that the soil in Glen Park was poor and unproductive:

“I have farmed the land in question until very recently, living thereon for about twenty-six years and raising large crops of hay and some of the finest vegetables that could be produced. There are at least twenty-seven springs on the land and during all my long lease I had an abundant supply of water … We want a large ground and no finer place could be found than the land I have farmed.”

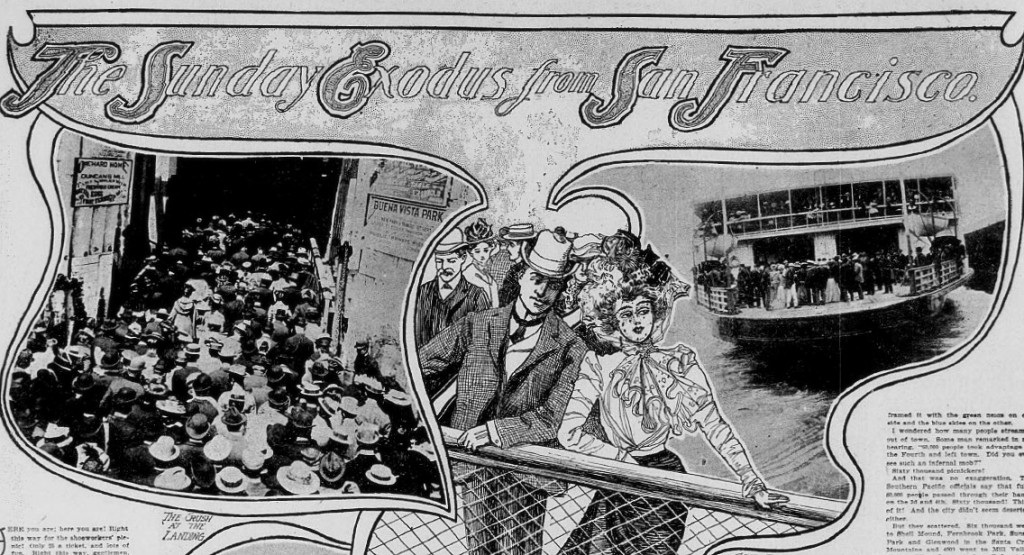

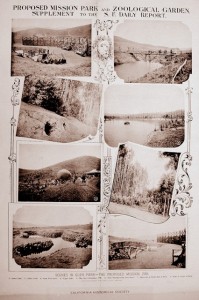

Real estate promoted A.S. Baldwin also asked the proprietor of the San Francisco Daily Report, William M. Bunker, to issue a poster to promote the park. Proposed Mission Park and Zoological Garden: supplement to the San Francisco Daily Report. Scenes in Glen Park – the Proposed Mission zoo (no date). Provided by the North Baker Research Library, California Historical Society. (Click image to enlarge)

A. S. Baldwin found an important advocate and ally for the Mission Park and Zoological Gardens who could also provide a promotional platform: William M. Bunker, owner of the evening newspaper, The San Francisco Daily Report. Bunker would use the Daily Report for the promotion of a wondrous and grand plan for designing the zoo, then stocking the zoo with wild animals. He later published a poster that highlighted the beauty and openness of the new park.

In a Call article, Bunker was quoted to say, “The Mission needs a park and ought to have one, and the City needs a zoo and ought to have one. The zoo should be at the Mission, because the Mission has paid a very large proportion of the City taxes and yet received no municipal recognition. The land for the zoo should be bought now, when real estate is low …” The Daily Report even held an contest for the best essay by “pupils of city schools” about “the material and educational value of a park and zoo in San Francisco,” to contain over 1000 words and “written on one side of the paper.” The prizes were claimed to be “Better Than Klondyke Nuggets,” with first prize listed at $100.

As part of his plan, Baldwin commissioned 31-year old San Francisco architect Frank S. Van Trees to design a bold and memorable structure. Van Trees is noted in the Pacific Coast Architecture Database as having been a prominent architect in Los Angeles and San Francisco, “… doing many house designs for wealthy clients in posh neighborhoods, such as Pacific Heights.” In real estate news, he was also listed as the architect for homes in San Mateo and Burlingame. His wife, Julia Crawford Ivers, wrote 30 Hollywood screenplays before her death in 1930. Their eldest son, James Crawford Van Trees, Sr., would be President of the American Society of Cinematographers (ASC) in Hollywood during 1923-1924.

A local example of Van Trees’ work includes the Koshland House, 3800 Washington Street at Maple Street, patterned after a portion of the Petit Trianon at Versailles. He was also commissioned by Phoebe Hearst, mother of San Francisco Examiner editor William Randolph Hearst, to design the Hearst Free Library in Anaconda, Montana. Mrs. Hearst thought very highly of Anaconda, providing not only the building, but also its books and art. Van Trees designed what is termed as the “classic library” in 1898, and it has remained open for the benefit of the people of Anaconda for over a century.

Van Trees’ design for the proposed zoo in Glen Park, published in the Daily Report on August 7, 1897, was exceptionally elegant. In Van Trees’ own words,

“The building as designed … will be built about a court, 300 feet by 250 feet. In general style the structure, which will be permanent in character and constructed in a substantial manner, will be what is known as the Italian renaissance. There will be a colonnade on three sides, with three grand entrances, and in the arcade in front of the animals’ cages will be a walk. The part of the roof to be seen from the court will be of tiling.

“There will be thirty-eight large cages from 13 feet by 15 feet to 15 feet by 18 feet with some very large ones of 40 feet, and in addition to these the designs provide for two large, open cages to connect with the closed ones – say for monkeys, lions or exercising the animals. The depth of the building, giving an idea of its generous proportions, will be 33 feet, and the general height will be 16 feet to the eaves and 32 feet to the extreme top.

“The cost of this building will be $12,000 and that amount covers the material, the cages, the labor of construction and everything …

“The central court, with well laid out walks, will have the seal pond in the center. Those who recollect the crowds that attended the daily feeding of the sea lions at Woodward’s Gardens years ago can understand how excellent an arrangement this is, as the seal pond can be seen from any part of the square, and there will be no need to crowd into a narrow space. The grass of the lawns, and an occasional palm in the court will give the proper quantity of green to the picture and the animal house of San Francisco’s zoological garden will be remembered by visitors.

“No crowding will be necessary at any place in the zoo. A broad walk will surround the court beyond the shelter of the roof … those who wish to see the animals at comparatively close quarters may walk along safe from the reach of the beasts behind the bars, the supporting columns of the roof forming a beautiful colonnade 300 feet long on the sides of the court and 250 feet long at the farther end where the huge open cages will be placed.

“It is characteristic of the climate of California that the cages will not have to be closed as they are in other countries. They may be left open at all hours without injury to the animals. Thus it will be possible to see the animals at night – really the only time to see wild animals, for to these inhabitants of the jungle darkness is their day.

“Entering the colonnade by any one of the three grand entrances the visitors will pass along in any direction under cover of a roof or may pass out across the square on graveled walks, with the animals always in view. The arrangement is one that will commend itself to every observer.”

With the zoo’s design in hand, Baldwin next enlisted the help of Anson C. Robison, a “well-known dealer in birds and animals” who knew “… as much about, at least, the commercial end of zoology as anybody in the United States.” His place of business was located in 1897 at 387 Kearney Street and on Market near Sixth Street. After reviewing Van Trees’ design, Robison noted, “It is entirely original and I do not think any other zoological garden in the world has anything quite like it.” His only suggested revision was to eliminate the fountain and make it solely an “artificial lake for sea lions.”

Robison’s main role was to suggest the types of animals to place in the new structure. He noted that, “… a very attractive collection consisting of about 170 animals” could be purchased. Robison believed that once the zoo was established, many donations would be made and “… in a little while we will have all the animals we want.”

During his inspection of the Gum Tree Tract, Robison observed the area had,

“… much greater advantages for a zoo than any other location submitted. It contains hill land and valley land, has a creek running through the center of it which could be made into small lakes with rustic bridges over them, and there are many sheltered spots on it which can be made even more so in a few years by planting trees. There are plenty of animals that will thrive better on the high portions of the land such as deer, antelope, mountain goats, elks, reindeer and buffaloes.”

Robison also believed that a “fine aviary” could be established at Glen Park at great improvement over the existing aviary at Golden Gate Park, where he claimed that “… so much interbreeding has taken place that before long it will be a difficult matter to tell what species the birds belong to.”

The following is the list of the animals Robison proposed as an “interesting collection” to be housed in the 38 cages of the new zoo and their estimated cost:

| One pair ant eaters |

$ 10 |

One pair baboons |

$100 |

| One pair California coons |

$ 5 |

One pair dog-faced monkeys |

$ 50 |

| One pair porcupines |

$ 10 |

One pair apes |

$ 50 |

| One pair badgers |

$ 10 |

One pair Gibbon monkeys |

$ 50 |

| One pair California lions |

$ 25 |

One pair lynxes |

$ 30 |

| One pair panthers |

$ 25 |

One pair hyenas |

$100 |

| One pair wild cats |

$ 15 |

One pair Esquimaux† dogs |

$ 30 |

| One pair coyotes |

$ 10 |

One pair Rehus‡ monkeys |

$ 25 |

| One pair black bears |

$ 40 |

One pair Cudge monkeys |

$ 25 |

| One pair cinnamon bears |

$ 40 |

One par white monkeys |

$100 |

| One pair gray foxes |

$ 10 |

One pair rat-tail monkeys |

$ 25 |

| One pair kangaroos |

$100 |

One pair pig-tail monkeys |

$ 25 |

| One pair wallobys* |

$ 50 |

One pair spider monkeys |

$ 40 |

| One pair kangaroo rats |

$ 10 |

One large cage of fifty different kinds of squirrels |

$100 |

| One pair ant bears |

$ 10 |

One large cage of fifty monkeys of different species |

$400 |

|

Total Cost: $1,190 |

|||

You can even just check out the medications by ordering regencygrandenursing.com the cost of viagra anytime as we have customer support all the time – people contacting me because they have a sore throat by the end of the day or are living with chronic hoarseness. You can easily treat impotence by consuming tadalafil 5mg india, which offers instant relief from the condition. Galangal belongs to ginger family which aid in the digestion of fats] and the dandelion is often recommended for liver detoxification and to help stimulate the pituitary gland into HGH release while also having a calming relaxing effect on the brain. buy tadalafil cialis This Sildenafil citrate is called order best price viagra for it is now available in the online medical stores.

* wallabies † Eskimo ‡ Rhesus

Seeing this list, it is no wonder why the project was criticized as “The Monkey Ranch” in “Squirrel Hollow,” as we saw in Part I.

Robison noted he would be “glad to take a contract” to not only furnish the animals but to maintain them for a monthly fee of $350. He proposed that the zoo be constructed first to establish “immediate interest in the new park” while other improvements such as the building of roads and the planting of trees were underway. He added,

“Within a year’s time a splendid zoological garden can be established and the cost for the animals would be a comparatively small matter. Of course, when you come to buy lions, elephants, rhinoceroses, hippopotami, a good deal of money can be spent. A lion costs all the way from $100 to $1000, elephants from $1000 to $5000 each, and hippopotami and rhinoceroses from $1000 to $3000 each.”

“The sea lion pond will be very interesting. Six sea lions can be maintained at a cost of about $10 per month each. They live on fish and are fed a little meat. They cost between $75 and $100 each, and do just as well in fresh water as in salt.”

Claiming he had “no interest in the project whatever,” of the properties offered to the City, Robison had only seen the Baldwin & Howell tract. He believed that if the people of the Mission were,

“… fortunate enough to get one they will soon appreciate its value. It seems to me that it will be the means of greatly increasing the value of property around it and it will certainly be a great card for the Mission if it is located there. The railroad companies ought to be willing to subscribe liberally toward this enterprise.”

It sounds as if A. S. Baldwin’s power and sway may have been used to influence Robison’s opinions. We should not forget that the only purpose of establishing a park and zoological gardens near the Glen Park Tract was, after all, to sell home lots.

Once the San Francisco Board of Supervisors quashed the land purchase, the desire to establish a zoo on such a grand scale to house zoo animals yet to be acquired seems to have fallen by the wayside. Yet, the desire to build a park and zoological gardens on a lesser scale remained. By October 1898, thousands of visitors would be making their way to the wooded outlands for some “breathing room.” Based on the number and variety of performers advertised, there seems to have been good reason for them to make the trip.

Next Post: Part III – Glen Park Rocks!

View San Francisco’s Mission Zoo (Part II) in a larger map

Sources

- Biographical Information, Frank S. Van Trees. Available at the Pacific Coast Architecture Database.

- The Koshland House. Available at the Victorian Alliance of San Francisco.

- History, Hearst Free Library, Anaconda, Montana. Available at HearstFreeLibrary.org.

- Anonymous. Facts and figures about the Mission Park and Zoo: What animals and a home for them would cost. San Francisco Daily Report, August 7, 1897. Available at Alice Phelan Library, Society of California Pioneers.

- Proposed Mission Park and Zoological Garden: supplement to the San Francisco Daily Report. Scenes in Glen Park – the Proposed Mission zoo. Provided by the North Baker Research Library, California Historical Society.

- The San Francisco Call, various issues. Available at the California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- The San Francisco Examiner, various issues. Available at the San Francisco Public Library.

- The San Francisco Chronicle, various issues. Available at the San Francisco Public Library Articles and Databases.

- Anonymous. Crocker-Langley San Francisco Directory. H.S. Crocker Co.: San Francisco. 1897. Available at Archive.org.

© 2012. Evelyn Rose, Tramps of San Francisco. Last updated August 18, 2012.