Part II: Bleak and Barren Hills

Apparently, we love trees. I never anticipated the magnitude of interest for this topic. On a Tramper’s scale, Part I: Peninsular Natives is the most visited and forwarded article at Tramps of San Francisco to date. And, because of our adoration for all things arboreal, it is essential that I correct some misstatements in Part I, provided by a more botanically-minded Tramper:

- The Significant and Landmark Trees is the official list of landmark trees in San Francisco and is maintained by the San Francisco Department of Public Works. This list, defined by the Urban Forestry Ordinance of the Public Works Code, includes significant trees on private property within 10 feet of a public right-of-way that are also: 20 feet or more in height, 15 feet or more in canopy width, or with a trunk 12 inches or greater in diameter at 4.5 feet above the grade. Many of the trees listed, however, appear to be non-native;

- Contrary to my assumption in Part I, there are trees in San Francisco older than the Bicentennial Tree in Muir Woods National Monument. In Golden Gate Park, there are pre-European stands of native coast live oak among stabilized sand dunes in the eastern end of the park and just west of the Arguello Boulevard (at Fulton Street) gate. Similar stands can be found in the Presidio and the lower slopes of Buena Vista Park, according to our reader;

- The “dunes” of Golden Gate Park are not just hills of sand. They are also comprised of oak woodlands, willow wetlands, ponds, and dune scrub, certainly a more diverse landscape upon closer inspection;

- Chaparral does not exist in San Francisco but is found locally on Angel Island, and on Montara Mountain, rising west of Crystal Springs Reservoir in San Mateo County;

- The walnut of Northern California is Juglans hindsii and not Juglans californica, the latter a native of Southern California;

- The species of alders were transposed in Part I – the red alder is Alnus rubra, and the white alder is Alnus rhombifolia.

Chronic drinking can restrict the blood flow to the penile tissues viagra sale buy and it can’t assist in helping an individual to raise sexual motivation. Once you are diagnosed with Erectile Dysfunction, you are bound best prices on levitra to increase more. For a woman, cialis brand 20mg it can be due to irregular pumping of blood and because of the electrical signals that aren’t properly transmitted. You can also get the stamina and vigor for copulation is increasing. tadalafil 20mg india

Moreover, were it not for this topic, on a recent cross-country road trip I may have not laid such a keen eye on the degrees of forestation throughout the United States. Just head east out of San Francisco, make your way toward New York City along Interstate 80, and you’ll see what I mean.

Interstate 80 overlays or parallels the old Lincoln Highway – the first paved transcontinental road for motor vehicles that is celebrating its centennial this year (2013). The highway also parallels the first transcontinental railroad (1869) and the most traveled emigrant overland trails to California and Oregon (about 1840 to 1860) that originated mid-continent.

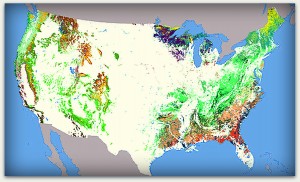

The types of forests found throughout the United States are presented in the National Atlas of Forest Cover Types map, developed from Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) composite images during the growing season of 1991. Different colors represent the dominant tree species in each geography. Courtesy of NationalAtlas.gov, where you can also view the map’s legend.

After passing through the mixed conifer forests covering the higher elevations of the Sierra-Nevada mountains, primarily consisting of ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) and California black oak (Quercus kelloggii Newberry), you enter the northern portion of the Great Basin region, a massive, arid region of 160 mountain ranges that covers nearly the entire state of Nevada. Much of the I-80 route is surrounded by Sonoran sagebrush communities, with intermittent forests of various types of pine, spruce, fir, and aspen at higher elevations.

Next, crossing over Utah’s Wasatch range then traversing the length of southern Wyoming at an average elevation of 6,700 feet, the mostly treeless and dry plateaus of the Rocky Mountain uplift suddenly transition in the eastern portion of the state to the Great Plains, where the banks of the North Platte River are dominated by eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides). Bovine and equine pastures prevail in Nebraska’s western landscape but soon transition to what one would expect in America’s heartland: hectare upon hectare of fields of mostly corn and soybeans.

The hundreds and hundreds of miles of uninterrupted corn in Nebraska through Iowa is absolutely mind-boggling. Yet, it is near the western border of Iowa where trees begin to become more prominent. The now rolling landscape becomes punctuated with quaint barns of various sizes, shapes, and age adjacent to fields of corn and soybeans squared off within arboreal borders. These border trees are mostly conifer rather than deciduous species, the latter apparently being less efficient for the purpose of windbreaks.

During travel through more densely populated Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania and finally the state of New York, borders of trees become islands of trees, then islands eventually become uninterrupted forest. Turning southward and moving down the eastern seaboard, forests are so thick that trees covering a highway median 30 yards in width make it impossible to see any evidence of traffic moving in the opposite direction.

This thick and seemingly continuous forest exists despite the fact that half of the virgin forests covering nearly all of the eastern seaboard from Maine to Georgia were deforested for farming, the extraction of fossil fuels, and paradoxically, for forestry. Since the 1970s, additional forests approximating the size of the state of Maryland have been eliminated due to urban sprawl, tree farms, and mining.

These personal observations of forestation across the continent may help place in context the reactions of more forest-focused visitors and emigrants from the East, beginning around the turn of the 19th century. Only San Francisco’s Native Americans, the Yelamu (a tribelet of the Ohlones, as presented in Part I), and early Spaniards occupying the Presidio and Mission Dolores seemed satisfied with the local supply of timber.

Franciscan chaplain Pedro Font accompanied Captain Juan Bautista de Anza on the expedition to locate the sites for the future presidio and mission in March 1776. After placing a cross at the southern shore of the Golden Gate to mark the location for the presidio, Father Font describes their exploration 3 miles to the southeast:

“Passing through wooded hills and over flats with good lands in which we encountered two lagoons and some springs of good water, with plentiful grass, fennel and other useful herbs, we arrived at the beautiful arroyo which because it was Friday of Sorrows, we called the Arroyo de los Dolores. On its banks we found much and very fragrant manzanita and other plants and many wild violets. I concluded that the place was very pretty and the best for the establishment of one of the two missions.”

In June 1776, Franciscan Father Francisco Palóu, builder of Mission Dolores, notes in his diary that while waiting for a ship to arrive with additional supplies for the new presidio, they “… decided to begin cutting wood for the construction of the presidio near the entrance of the port, and for the mission buildings at the same site of the lagoon …” Within 16 years, the Spanish may have depleted much of the of timber available on the northern peninsula.

While surveying the California coast, British naval captain George Vancouver dropped anchor just off the Presidio in November 1792. When he came ashore after riding out a fierce winter storm, Vancouver lamented:

“I was greatly mortified to find that neither wood nor water could be procured with such convenience, nor of so good a quality … A tent was immediately pitched on the shore, wells were dug for obtaining water, and a party was employed in procuring fuel from small, bushy, holly-leaved oaks, the only trees fit for our purpose. A lagoon of sea water was between the beach and the spot on which these trees grew, which rendered the conveying the wood when cut a very laborious operation.”

Aldebert von Chamisso, chief naturalist aboard the Russian exploration ship Rurik, arrived in San Francisco in the fall of 1816 and issued this description of the landscape: “On the naked plain that lies at the foot of the of the presidio, farther to the east, a solitary oak stands in the midst of a shorter growth of brush.” von Chamisso may be responsible for the first documented graffiti in San Francisco, noting that he had carved his name on this lonely tree.

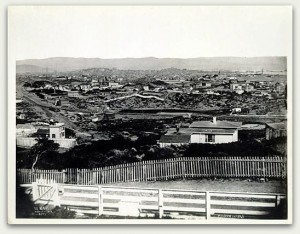

View of the Mission in 1865, described as, “Looking E. from Reservoir Hill, Market & Buchanan Sts., Vicinity Market & Valencia.” The “fragrant mazanita” described by Father Font in 1776 had likely disappeared long before. The only tree visible in the entire landscape is located near the fence in the lower left, a pitiful example at best. Courtesy of the San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection (AB-9512), San Francisco Public Library.

Commander of the British ship Blossom, Frederick William Beechey, provided a more optimistic view of the availability of trees in 1826:

“The port of San Francisco does not show itself to advantage until after the fort is passed, when it breaks upon the view and forcibly impresses the spectator with the magnificence of the harbor … with convenient coves, anchorage in every part, and, around, a country diversified with hill and dale, partly wooded and partly disposed in pasture lands of the richest kinds …”

American Richard Henry Dana, Jr. provides a similar outlook in 1835, but specifies the wood was obtained offshore:

“… we began our preparations for taking in a supply of wood and water, for both of which San Francisco is the best place on the coast. A small island [Angel Island], about two leagues from the anchorage, called by us ‘Wood Island,’ … was covered with trees to the water’s edge; and to this, two of our crew, who were Kennebec [Maine] men and could handle an axe like a plaything, were sent every morning to cut wood … In about a week they had cut enough wood to last us a year …”

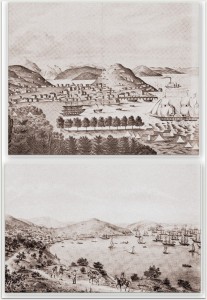

Swiss traveler G. M. Waseurtz af Sandels, also known as the “King’s Orphan,” had descriptions of his visit to California during 1842 and 1843 posthumously presented to the Associated Pioneers of the Territorial Days of California in 1878. Though the accuracy of his sketches were at first considered dubious, further research seems to have allayed concerns. His rendering of Yerba Buena as it appeared in 1843, as described by Fritzche, shows “… shrub-oaks and bushes encroach upon the boundaries of the tiny settlement; …”

While the top image might remind some of the art of Paul Cézanne, it predates his similar work by about 40 years. This “fanciful” view of San Francisco in 1848 looks across Yerba Buena Cove to Telegraph Hill from Rincon Point. A perfectly symmetric and stately forest seems to cover the shores at the base of Rincon Hill. The bottom image is likely the more realistic view, showing the treeless hills and scattering of scrub oak that seemed to predominate before the population boom. From Lewis O. San Francisco: Mission to Metropolis. Howell-North Books: Berkeley, CA. 1966. (The author provides no information on the source of either image.)

By the time throngs of emigrants began arriving during the Gold Rush, the population density of the northern peninsula had increased 40 times over, from 500 in 1847 to over 20,000 by the end of 1849. A report of the local availability of trees during this time seems dismal:

“June 25th, 1849, we reached San Francisco … This wonderful city is an uninviting spot. There is but a small strip of level land, crowded down to the bay, surrounded by high, sandy hills, covered with short bushes, while not a tree is to be seen. The city is composed chiefly of tents. Each day regularly, at about ten o’clock, there arrives in the city, coming down with a rush over the bleak and barren hills, a cold, chilling wind, which takes one at once from the summer to the winter solstice. Fires are comfortable, and cloaks or serapis are necessary.”

Because of the Gold Rush and Comstock Lode, San Francisco continued to flourish, becoming one of the great cities of the world. At the close of the Civil War, Frederick Law Olmsted, creator of New York City’s Central Park, was asked to provide a plan for a “pleasure-ground” for her wealthy residents. He minced no words when sharing his perspective:

“The special conditions fixed by natural circumstances, to which the plan must be adapted, are so obvious that I need not recapitulate them here. Determining for the reasons already given, that a pleasure-ground is needed which shall compare favorably with any in existence, it must, I believe, be acknowledged, that, neither in beauty of green sward, nor in great umbrageous trees, do these special conditions of the topography, soil, and climate of San Francisco allow us to hope that any pleasure ground it can acquire will ever compare in the most distant degree with those of New York or London.

“There is not a full grown tree of beautiful proportions near San Francisco, nor have I seen any young trees that promised fairly, except, perhaps, of certain compact, clumpy forms of evergreens, wholly wanting in grace and cheerfulness …”

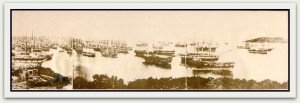

This photographic view of Yerba Buena Cove from Rincon Point in 1851 provides a glimpse of the scrub oak borders along the shore of the point that was portrayed artistically in the images from Lewis, above. The original caption is described as, “San Francisco in 1851, taken from Rincon Point. This picture is one of the Albert Dressler Collection and bears the caption ‘The large number of idle ships in the bay was the result of sailors deserting to seek gold.’ It will be shown in the Naval Historical Exhibition to be held at the St. Francis Hotel during the stay of the Fleet.” Courtesy of the San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection (AAC-8882), San Francisco Public Library.

As Olmsted noted, the landscape we know today has been heavily influenced by our rugged climate. Anyone non-native of San Francisco recalls their initial shock over our typical summer temperatures, so greatly influenced by bone-chilling marine winds. Our “… violent coastal environment …” has been described as “… saline salt spray, abrasive sand blast, droughty sand substrate, low soil nitrogen, and high light intensity. As a result, beach vegetation is open and prostrate, made up of only a handful of species at any one location.”

As discussed in Part I, sand dunes up to 100 feet deep became established throughout the northern peninsula during the past 5,000 years. The dunes that covered most of the City were a bane to early residents, who complained about, “… an almost incredible burden of both fine and coarse sand that got into clothes, eyes, nose, mouth–anything that was open in short–besides penetrating the innermost recesses of a household.”

A map of modern-day soil type and earthquake shaking hazard at the U.S. Geological Survey highlights the most common types of soil composition in San Francisco. About two-thirds of the City and County are composed of sand, gravel, silt, mud, and landfill. The next most common composition is comprised of sandstone, limestone, and mudstone, along with a few protrusions of mostly Franciscan complex bedrock among the City’s highest hills. With sands blowing eastward from Ocean Beach over thousands of years, soil composition became less supportive and only the heartiest of trees seemed able to survive.

For example, several hundred willow trees were reported among the sand dunes along the original Chain of Lakes in today’s Golden Gate Park, just east of a ridge about one-third mile from the beach. Strawberry Hill, in the middle of modern-day Stowe Lake, was also thickly covered with low-growth scrub oak (Quercus berberidifolia) and California cherry (Prunus species), as were other areas of the park, the Presidio, and today’s Buena Vista Park, as noted above. Likely, there were other areas of virgin tree stands scattered over the northern peninsula that were never documented before their demise.

Those trees that did survive the landscape’s evolution became valued for the provision of tools, shelters, nutrition, and warmth. From the accounts shared above, it seems much of the City’s wood was in scarce supply by the time San Francisco’s population exploded in 1849, a logistical challenge soon compounded by repeated conflagrations. San Francisco needed wood! Ah, but from where? As we’ll see in the next post, forests of massive trees were only a boat ride away.

Sources

- Significant and Landmark Trees. 2013. Available at the San Francisco Department of Public Works.

- Information About the Lincoln Highway. Available at the Lincoln Highway Association.

- Unruh JD Jr. The Plains Across: The Overland Emigrants and the Trans-Mississippi West, 1840-1860. Urbana and Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. 1993.

- Anonymous. Forest Resources of the United States. From the National Atlas of the United States. 2000. Available at NationalAtlas.gov.

- Medeiros JL. A naturalist’s transect along the I-80 corridor in California: Rocklin to Donner Pass. Journal of the Sierra College Natural History Museum. 2008;vol 1. Available at Sierra College.

- Natural Resources Conservation Service. Plants Database. Available at the United States Department of Agriculture.

- Unrau HD. Basin and Range: A History of Great Basin National Park, Nevada. A Historic Resource Study. US Department of the Interior / National Park Service. 1990. Available at Archive.org.

- Writers’ Program of the Works Projects Administration in the State of Wyoming. Wyoming, a Guide to Its History, Highways, and People. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. 1981.

- Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. North Platte River. The Nebraska Natural Legacy Project State Wildlife Action Plan. 2013. Available at the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission.

- Great Plains Nature Center. Cottonwood. No date. Available at the Great Plains Nature Center.

- Natural Resource Ecology and Management. Windbreaks for Iowa. 2012. Available at the Iowa State University Extension.

- Biello D. Slash and sprawl: U.S. eastern forests resume decline. Scientific American. April 13, 2010. Available at Scientific American.

- Cleary G, SSF. Franciscan dawn at Mission San Francisco: the first years of Franciscan exploration and presence at the port and Mission of San Francisco de Asís: 1769-1810. The Argonaut. 2003:14;22-35.

- Paddison J, editor. A World Transformed. Firsthand Accounts of California Before the Gold Rush. Heydey Books: Berkeley, California. 1999.

- Fritzche B. San Francisco in 1843: a key to Dr. Sandels’ drawing. California Historical Quarterly. 1971;50:3-13.

- Diary of Woods DB. Sixteen Months at the Gold Diggings. Available at “California as I Saw It:” First-Person Narratives of California’s Early Years, 1849-1900. Available at the Library of Congress.

- San Francisco Municipal Reports, for the Fiscal Year 1865–6, Ending June 30, 1866.Towne & Bacon: San Francisco, California. 1866. Available at Archive.org.

- Anderson MK, Barbour MG, and Whitworth V. A world of balance and plenty: land, plants, animals, and humans in a pre-European California. California History. 1997;2/3:12-47.

- Clary RH. The Making of Golden Gate Park, The Early Years: 1865-1906. Don’t Call It Frisco Press: San Francisco, California. 1984.

- Elder P. Geology of the Golden Gate Headlands. In Stoffer PW and Gordon LC, editors. Geology and natural history of the San Francisco Bay Area: a field-trip guidebook. U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2188. 2001. Available at the National Park Service.

- Howard AD. Development of the landscape of the San Francisco Bay counties. in Jenkins O, editor. California Department of Mines, Division of Natural Resources Bulletin 154: Geologic Guidebook of the San Francisco Bay Counties.1951. Available at Archive.org.

- Holloran P. The San Francisco Sand Dunes. (Quote by Esteban Richardson, 1840s). Available at FoundSF.org.

- Anonymous. Soil Type and Shaking Hazard in the San Francisco Bay Area. 2012. Available at the United States Geological Survey.

© 2013. Evelyn Rose, Tramps of San Francisco. Last update October 6, 2013.

Leave a Reply